Last week, the U.S. State Department issued the 2023 Trafficking in Persons Report. This annual report is a critical tool to monitor and assess efforts to eliminate human trafficking. As investors, we expect companies, in the course of their human rights due diligence, to act based on the report’s identification of salient risks to people in their operations and supply chain. In her message at the beginning of the report, Ambassador Cindy Dyer wrote:

Getting ahead of the traffickers requires us—governments, civil society, front-line workers, and the private sector—to harness advanced tools and to forge new relationships. Effective partnerships manifest the power to transform anti-trafficking efforts from prevention to protection to prosecution.

Message from the Ambassador-at-Large, 2023 Trafficking in Persons Report

One of the more insightful commentaries on the new TIP Report comes from Martina E. Vandenberg, founder and president of The Human Trafficking Legal Center. In the coming days and weeks, we’ll see more analysis and commentary, but I’d like to highlight one innovation in this year’s report: a section entitled “Deceiving the Watchdogs: How Unscrupulous Manufacturers Conceal Forced Labor and Other Labor Abuses” (pp 50-52). This section highlights the limits of supply chain social audits conducted by companies and third-party providers. The report identifies “a cottage industry” to help factories “pass” the audits by falsifying records, concealing passport retention, and manipulating workers, among other tactics. Among the nine recommendations proposed in the report, six point toward worker-led social responsibility. A more substantive human rights due diligence, I believe, captures the spirit of “partnership” called for by Ambassador Cindy Dyer.

When SGI members talk with companies about their human rights due diligence, most companies trumpet their codes of conduct. Those documents herald a “zero tolerance” for forced labor, prison labor, and child labor. The codes outline a regime of factory social audits to document compliance. The companies may even lift up the silence in reports from their grievance mechanism as proof of their success. For years, we have been telling companies that these are not adequate measures. Those measures exist to protect the company, but additional measures are required to protect people in the supply chain. Companies need to “pay attention,” as attention is owed to people who are endangered. A code of conduct and social audits are necessary but insufficient for human rights due diligence.

That reliance on social audits is insufficient to protect rights holders ought to be self-evident based on front-page news. Operation Blooming Onion uncovered dozens of trafficked persons in criminal acts that reaped more than $200 million. Other recent events, just in the U.S., include:

- US Department of Labor investigation results in judge debarring North Carolina farm labor contractor for numerous guest worker visa program violations(US Department of Labor, 3/16/21 – judgment against H-2A LC) “Sleepy Creek Farms provides berries to retailers such as Trader Joe’s, Harris Teeter, Driscoll’s, and Food Lion, among others.”

- Lancaster Meat Processing Plant Endangered Minors By Allowing Them To Perform Hazardous Tasks, Work More Than The Law PERMITS(US Department of Labor, 2/14/23) “Located in Central Kentucky, Marksbury Farm Foods LLC distributes food in Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana and Michigan, including at Kroger and Whole Foods Market locations.”

- Court Sentences Florida Labor Contractor To Nearly 10 Years In Prison In Case Involving Forced Labor, Part Of US Department Of Labor Investigation(US Department of Labor, 2/2/23 – criminal conviction against H-2A LC.) “Los Villatoros Harvesting LLC employed workers to harvest watermelons for Carlton Farms Inc., operating as Sun Fresh Farms Inc. in Wauchula, Florida, for sale to Walmart and Kroger locations. In Indiana, the employer provided crews for Cardinal Farms in Oaktown and Wonning Melons in Vincennes to pack melons for sale through a distributor to chains including Kroger, Schnucks and Sam’s Clubs.”

- Federal Investigation Finds Oregon Labor Contractor Violated Multiple Federal Laws Related To Van Crash That Killed Three Migrant Farmworkers(US Department of Labor, 4/26/21) “The division found that JMG Labor Contractor of Salem had employed the workers at Holiday Tree Farms, a large Corvallis-based grower of Christmas trees sold at Home Depot and Costco stores.”

W e have seen how child labor cases have increased significantly in the United States over the past five years. A recent investigation by the New York Times found children working exhausting and often highly dangerous jobs across the United States in violation of child labor laws.

Simply put, a company that performs worker-focused human rights due diligence shows that it better understands social-related risks and opportunities in general and the extent to which it is equipped to identify and manage these issues more effectively than a company that relies on its code of conduct and social audits. Too many companies continue to rely on this discredited approach, and workers pay the price as companies cling to an ineffective model that fails to protect human rights. Worker voice plays a critical role in addressing supply chain abuses, as exemplified in the success of the Fair Food Program and the International Accord.

We are glad that the 2023 TIP Report joins the chorus of those calling for a worker-centered human rights due diligence.

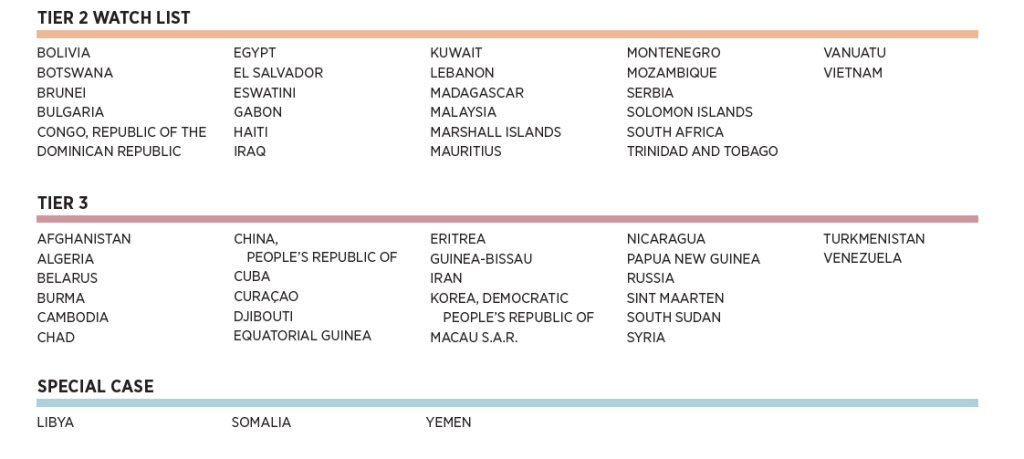

As always, the largest component of the report is a series of country-by-country technical assessments. The report categorizes 188 countries and territories with regard to their compliance with the standards of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) of 2000. Each country is tiered according to compliance:

- Tier 1: those governments who fully comply with the TVPA’s minimum standards

- Tier 2: while not fully complying, governments with significant efforts to bring themselves into compliance with those standards

- Tier 2 watch list: not fully complying along with a significant absolute number of trafficking victims, or a failure to increase efforts, or a determination that the country is in fact committed to making significant progress in the coming year

- Tier 3: those governments who do not fully comply with the minimum standards and are not making significant efforts to do so

- Special cases: countries where a civil or humanitarian crisis makes gaining information difficult

Tier 1, which includes the United States, is simply compliance with the minimum standards. A tier 3 designation means that the U.S. can restrict assistance or withdraw support for the country at global funding organizations like the International Monetary Fund.

The report includes a country by country analysis of human trafficking and intends to offer “homework” to governments based on their tier. The image above lists the countries of the tier 2 watch list, tier 3, and special case categories.

To read about a previous year’s TIP Report, please see the 2021 edition here, 2020 edition here, and the 2019 here.